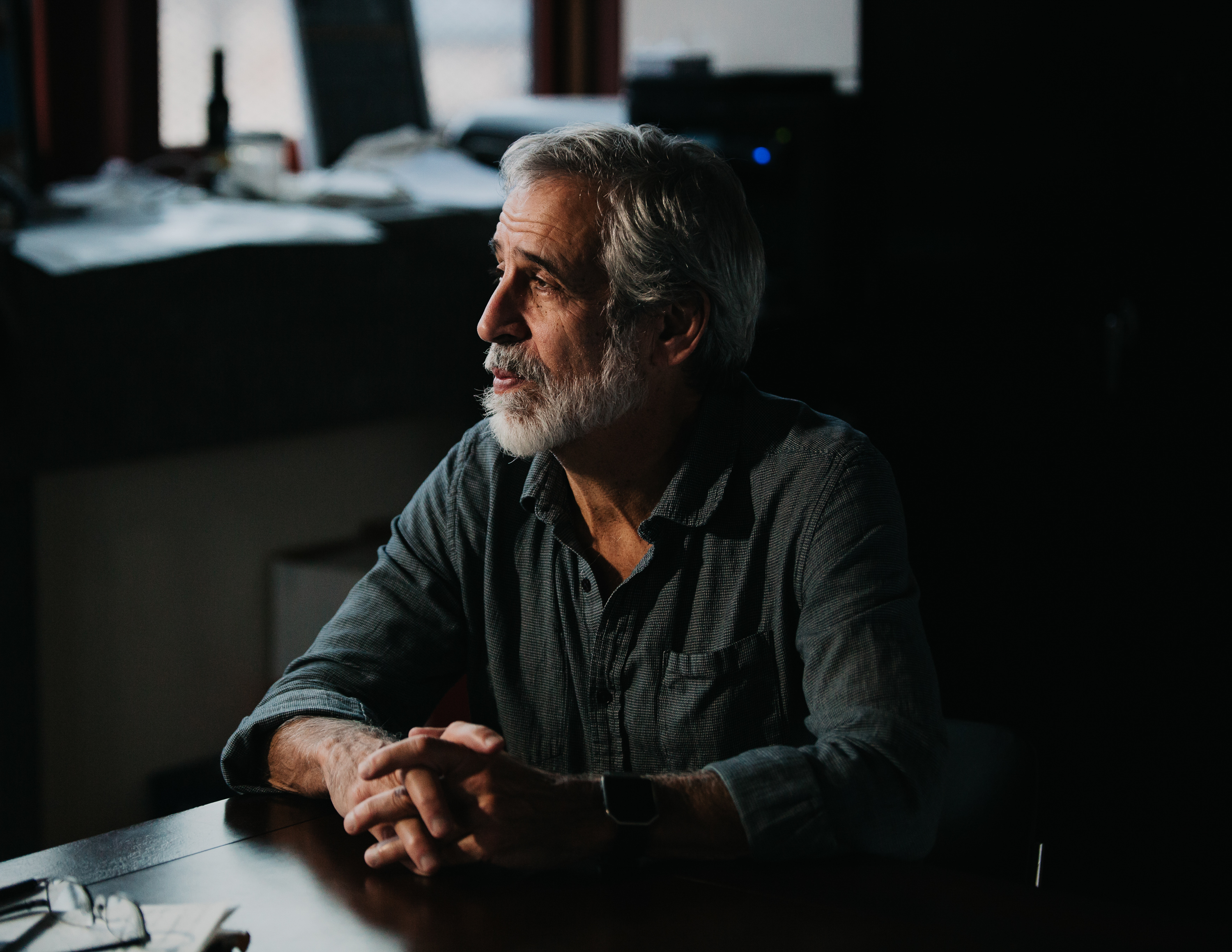

Interview by Michael Miner

Photos by Kevin Serna

I first heard the name Laquan McDonald from a whistleblower who contacted a colleague of mine. Two or three weeks after the [October 2014] shooting, I stood at 41st and Pulaski, the shooting site, and asked myself, “What happened here?” Over time I found a civilian witness who was very credible, and ultimately I got the autopsy report, and began to piece together the story. We often use the term “code of silence,” but it’s really a matter of narrative control. From the moment Laquan McDonald lay bleeding out on the ground, a narrative was forming about what happened, and within hours the city put out an account that was completely false about an aggressive, erratic young man who threatened the police. In order to sustain that false narrative, it proved necessary to intimidate witnesses, destroy evidence, falsify police reports, withhold public information from the public, stonewall the press, and, ultimately, pay out a $5 million settlement to the family in an effort to keep the video from coming out. Yet in the end, the official narrative utterly and completely cratered, and with it the political power of various actors—the mayor, the state’s attorney, the superintendent of police—creating a whole new political landscape in Chicago. A space was created for truth telling about the underlying conditions that allowed the shooting.

I think “cover-up” is not the right description of what happened. A cover-up is a discrete set of conspiratorial and criminal acts. This was standard operating procedure. The press likes to describe everything as a crisis, but in this instance the crisis is that there is no crisis. A crisis is a departure from the norm, and what we’re contending with is the norm. It’s our increased clarity about the underlying nature of the institutional racism we’re confronting that is so daunting and challenging, and at the same time such an opportunity. If we can tell the truth about these conditions, we gain power to fix them. In that sense, this is a moment of great opportunity—and also peril.

The election of Trump certainly increases the peril, but it may also increase the clarity we need to be effective. I’m among the legions of people who were shocked by the election. We woke up Wednesday in a different country. I’m pretty strategic—my inclination is to think one door closes, another door opens—but it’s important now to take time to absorb what’s happened and to grieve. I’ve spent the last 20 years writing about people living under a de facto apartheid justice system in abandoned neighborhoods on the south side of Chicago. There’s something strangely familiar about this moment of joining the disenfranchised.

The election of Trump certainly increases the peril, but it may also increase the clarity we need to be effective. I’m among the legions of people who were shocked by the election. We woke up Wednesday in a different country. I’m pretty strategic—my inclination is to think one door closes, another door opens—but it’s important now to take time to absorb what’s happened and to grieve. I’ve spent the last 20 years writing about people living under a de facto apartheid justice system in abandoned neighborhoods on the south side of Chicago. There’s something strangely familiar about this moment of joining the disenfranchised.

The big danger is that we will normalize what’s happened. I want to resist that. We should assume Donald Trump means what he says. Think of all the columns written in recent days speculating that he will govern differently than he ran for office. I’m not going there. I’d love to be proved wrong, but my assumption is that we’re going to be living under a classic authoritarian regime.

With this election, we’ve joined the rest of the world. Think of all the other nations that live under moronic, venal leadership. There are models for honorable political lives in those circumstances, but those models are quite different from our dominant notions of citizenship in which we follow politics as a spectator sport and occasionally vote. All over the world there are people in repressive settings who find ways to live as free human beings, act in solidarity with their neighbors, and fashion strategies to resist state power. We’re going to need to get good at practicing that kind of politics.

One of the dangers is that people will instead become demoralized and retreat into denial, that they will seek refuge amid the pleasures and fulfillments of private life. That would give carte blanche to power. There was a term used in central Europe to describe those who opted to retreat into private life under totalitarianism. They were called “internal emigres.” That is certainly tempting at a time like this: to live one’s life in the wholly private realm, enjoying the company of friends, good food and drink, the pleasures of literature and music, and so on. Privileged sectors of our society are already heavily skewed that way. It’s a real danger at a time like this. If we withdraw from public engagement now, we aid and abet that which we deplore.

The sea change at the national level comes at a moment of extraordinary opportunity in Chicago to address fundamental issues of racism in our institutions and culture. It’s a question whether we will rise to the occasion. I think that the changes in Washington—I’m looking for a word besides catastrophe—do, in ways we have yet to fully understand, reconfigure the field of play in Chicago. It’s highly unlikely the Department of Justice will do more than issue a report based on its investigation of the Chicago Police Department. The prospect of vigorous federal oversight embodied in a consent decree has largely evaporated. It’s hard to imagine Trump’s Justice Department being interested in negotiating reforms of the Chicago Police Department.

We can expect increasing militarization of the police. Nationally, the political gravitational field is going to be dominated by powerful law-and-order themes, lock-’em-up themes, support-our-police themes. There will be very little interest in a reform agenda. So even if there was a disposition by Trump’s Justice Department to oversee reform in Chicago, it’s not clear we’d want that.

The truth is that much of the relatively well-spoken, “responsible” Republican establishment in Congress has been just as racist, but they’ve abided by a set of political conventions. Now we clearly see the nature of the forces we’re contending with. The Trump phenomenon has put race—the great unresolved blood knot of racial inequality—front and center. It’s released appalling toxins into the body politic. But at the same time it’s allowed for greater clarity on the part of those with the will to resist what’s coming. v

![[photo of camiella williams]](https://people.chicagoreader.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Camiella_Williams-1-150x150.jpg)